Disclaimer: This post is for academic purposes only. Please read the original document if you intend to use them for clinical purposes.

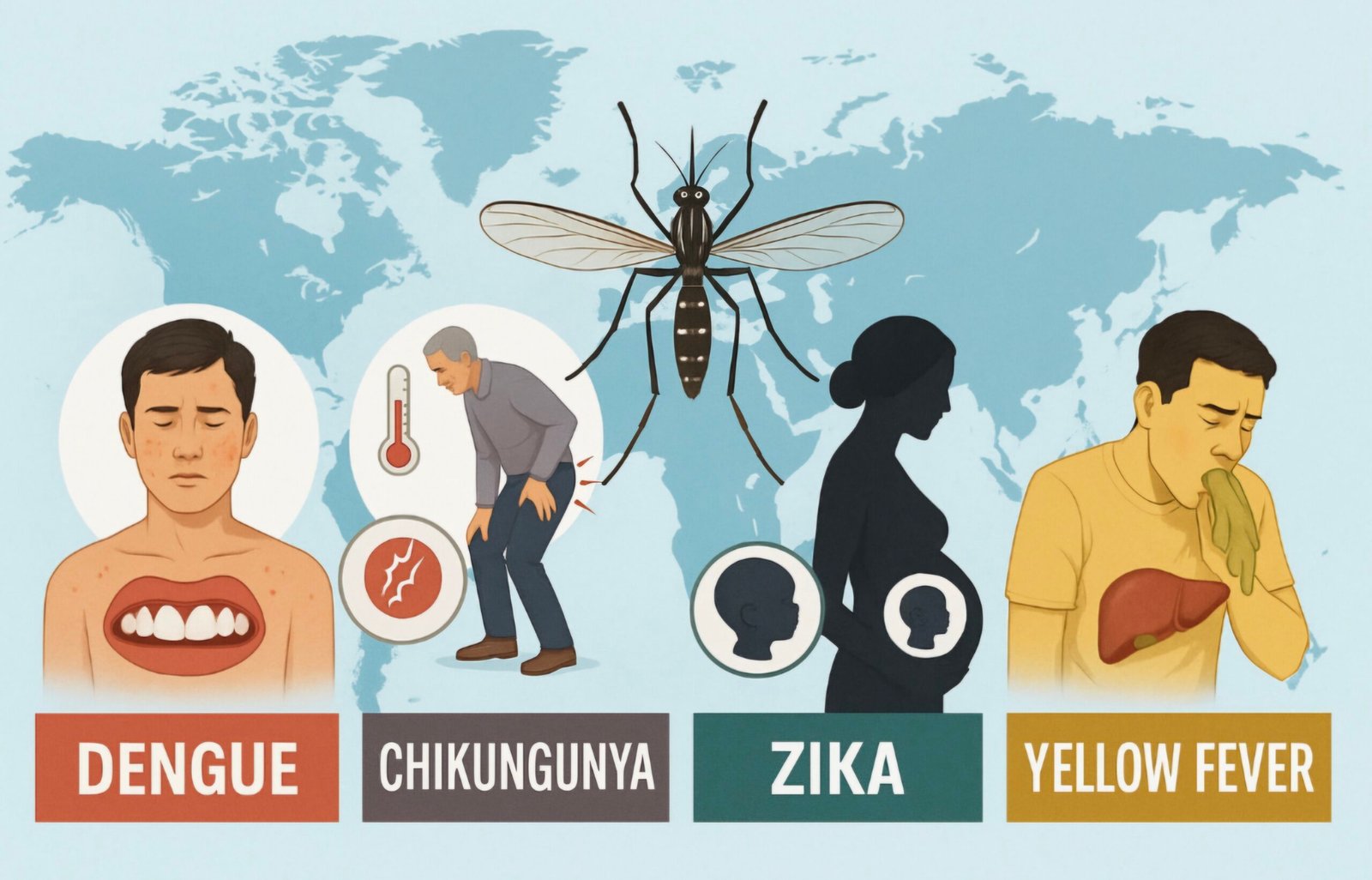

This document summarises the guideline for the clinical management of arboviral diseases, specifically Dengue, Chikungunya, Zika, and Yellow fever. It focuses on diagnosis and treatment, with an emphasis on systematic review of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). The guidelines were developed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, which commissioned a systematic review of RCTs on clinical diagnoses and treatment for arboviral diseases.

Specific Arboviral diseases and their manifestations

The document acknowledges the distinct clinical manifestations of different arboviral diseases, while also highlighting shared characteristics.

- Dengue:

- It is endemic in 10 countries in the South-East Asia Region and 23 countries in the Western Pacific Region, with significant increases in cases observed in Bangladesh, Thailand (2022-2023), Indonesia, and India (2024).

- Severe disease: those patients who clinicians assess as requiring hospitalization based on a clinical evaluation which includes assessment for the presence of warning signs and existing complications. These are:

- Dengue with warning signs:

- Abdominal pain: progressive until it is continuous or sustained and intense, and at the end of the febrile stage

- Sensory disorder: irritability, drowsiness, and lethargy

- Mucosal bleeding: bleeding gums, epistaxis, vaginal bleeding not associated with menstruation or more menstrual bleeding than usual and haematuria

- Hepatomegaly: more than 2 cm below the costal margin and abrupt onset

- Vomiting: persistent (three or more episodes in one hour or four episodes in six hours)

- Progressive increase in haematocrit: on at least two consecutive measurements during patient monitoring.

- Dengue with criteria of severe disease, according to the WHO 2009 definition

- Oral intolerance

- Difficulty breathing

- Narrowing pulse pressure

- Arterial hypotension

- Acute renal failure

- Prolonged capillary refill time

- Pregnancy

- Coagulopathy

- Dengue with warning signs:

- Dengue is specifically noted as involving plasma leakage in some patients, a clinically significant degree of plasma leakage due to increased capillary permeability

- Chikungunya, Zika, and Yellow Fever:

- These are listed alongside dengue, indicating their inclusion in the guideline’s scope.

- The document provides clinical manifestations of Dengue, Chikungunya , Zika and Yellow Fever which differentiate them from other causes of febrile illness. It categorizes findings into Moderate and Low for their differentiating power. For instance, Haemorrhage (includes bleeding on the skin, mucous membranes, or both) is a Moderate finding for Dengue, while Arthralgia is a Moderate finding for Chikungunya.

General Management Principles and Treatment Considerations

The guidelines discuss various treatment modalities and their evidence base, often highlighting the uncertainty due to limited or low-certainty evidence, particularly from RCTs.

- Fluid Management:

- ORS (Oral Rehydration Solutions): ORS are preferred for electrolyte replacement. If unavailable, other fluids as locally available may be used in addition to water, including soups, unsweetened fluid juice, coconut water, yogurt drinks, and water used after cooking of rice or grains.

- Avoidance: Avoid commercial carbonated drinks that exceed the isotonic level (5% sugar) as they may exacerbate hyperglycaemia related to physiological stress from dengue and diabetes mellitus. Examples include commercial carbonated beverages, commercial fruit juices and sweetened tea.

- Intravenous Fluid Volume: Guidelines are provided for guiding the administration of intravenous fluid volume

- Crystalloids vs. Colloids: The document lists interventions assessed, including Balanced crystalloids (Ringer’s lactate), Dextran, Starch, Isotonic saline, Gelatins, and Hypertonic saline. Colloids may have little or no impact on mortality, and may have little or no impact on organ failure. There is “Low” certainty of evidence for these conclusions. Colloids may lead to an increase in Severe adverse events (mostly infusion reactions)

- Lactate-Guided Resuscitation:

- Lactate-guided resuscitation, compared with standard of care in two trials reporting data from 430 participants, probably decreases mortality (4 fewer deaths per 1000, CI 95% 8 fewer – 0 more).

- Lactate-guided resuscitation may decrease ICU length of stay (1.5 fewer mean days, CI 95% 3 fewer – 0.1 fewer).

- Lactate is not readily measurable in many low-resource settings.

- Lactate is not useful for fluid monitoring in the context of liver failure, including yellow fever.

- Passive Leg Raise (PLR) Test:

- This test is used to assess fluid responsiveness in patients with shock.

- Protocol involves positioning the patient semi-recumbent at 45°, recording cardiac output, quickly lowering the patient flat and lifting both legs to at least 45°, and recording cardiac output again within 30-90 seconds.

- Known limitations of the test are severe hypovolaemia (where volumes of venous blood in the legs are small), and where intra-abdominal pressure is raised.

- Pain and Fever Management:

- Paracetamol (Acetaminophen):

- A large amount of data on pregnant women indicates neither malformative nor foetal /neonatal toxicity.

- If clinically needed, use paracetamol during pregnancy at the lowest effective dose, for the shortest possible time and at the lowest effective frequency.

- Uncertainty remains regarding whether paracetamol increases or decreases severe bleeding and acute kidney injury due to extremely serious imprecision in the evidence.

- Metamizole (Dipyrone):

- Causes similar fever reduction to NSAIDs (moderate certainty).

- Concerns about safety, specifically inducing agranulocytosis, have led to market withdrawals in several countries (e.g., UK, Canada, US, India).

- Still readily available in Spain, Russia, Israel, and many countries in Latin America.

- Evidence on aplastic anemia impact is “low certainty.”

- Not recommended in the third trimester of pregnancy due to fetotoxicity.

- NSAIDs (Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs):

- Whether NSAIDs treatment increases severe bleeding in patients with non-severe arbovirus disease is uncertain (1 more case per 1000 patients, 95% CI 1 fewer to 3 more, very low certainty).

- Evidence was limited to dengue and indirectly applied to other arboviruses.

- Paracetamol (Acetaminophen):

- Specific Therapies (for Severe Disease):

- Corticosteroids:

- In patients with severe arboviral disease, it is uncertain whether steroids increase or decrease mortality.

- Corticosteroids probably increase gastrointestinal bleeding (11 more per 1000, 95% CI 1 more – 3 more, moderate certainty).

- Immunoglobulins (IVIG):

- uncertain whether immunoglobulins increase or decrease mortality.

- uncertain whether immunoglobulins increase or decrease severe bleeding.

- uncertain whether immunoglobulins increase or decrease adverse events.

- Platelet Transfusion:

- The GDG considered that there is no evidence to support the prophylactic use of platelet transfusion outside the context of ongoing bleeding.

- Prophylactic use in the absence of bleeding may be appropriate in specific circumstances, for example preceding a surgical procedure with anticipated blood loss.

- A threshold of 10 000 platelets per microlitre was discussed for prophylactic platelet transfusion based on earlier WHO recommendations.

- uncertain whether platelet transfusion increases or decreases mortality, severe bleeding, or clinical bleeding.

- Potential harms include risk of transfusion-transmitted infections and further risk of fluid overload.

- N-acetylcysteine (NAC) for Yellow Fever (Liver Failure):

- It is unclear whether N-acetylcysteine treatment might improve the prognosis for patients with liver failure secondary to yellow fever virus infection.

- Uncertainty exists regarding its impact on mortality, mechanical ventilation, liver transplant, and severe bleeding.

- N-acetylcysteine is on the WHO’s List of Essential Medicines and is available as an inexpensive generic drug.

- Dosage guidelines are provided for different body weights and infusion schedules.

- Corticosteroids:

Research Needs and Limitations

The document explicitly outlines areas where further research is needed and acknowledges limitations in the current evidence.

- General Research Needs: Includes defining disease phenotypes for guiding patient management, understanding volume resuscitation phases in dengue shock syndrome, and exploring the role of hematocrit.

- Chikungunya Research: Specifically needs evaluation of NSAID use for pain control in post-acute phases and assessment of optimal strategies for Disease Modifying Anti Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) in chronic stages.

- Limitations in Evidence: For most Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) questions, there were no RCTs identified, leading to low certainty of evidence for many recommendations.

- Minimal Important Difference (MID): The GDG defined MIDs for various outcomes (e.g., length of hospital stay, mortality, organ failure) to guide interpretation of intervention impacts

Conclusion:

This guideline provides comprehensive recommendations for the clinical management of common arboviral diseases. While emphasizing evidence-based practices, it frequently highlights the significant gaps in high-quality research, particularly randomized controlled trials, for many interventions. This uncertainty underscores the importance of clinical judgment and individualized patient care, especially in resource-limited settings where some diagnostic tools or treatments may not be readily available. The document also clearly articulates the need for further research to strengthen the evidence base for managing these critical public health threats.

Citation: WHO guidelines for clinical management of arboviral diseases: dengue, chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Answers of MCQs of previous post:

Question 1): A 25-year-old patient presents with fever for 3 days in an endemic area. Which of the following is the MOST appropriate initial diagnostic test for dengue virus detection in the acute phase (0-7 days post symptom onset)?

A) IgM ELISA

B) IgG antibody detection

C) NS1 antigen detection by ELISA/RDT

D) Plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT)

Answer: C) NS1 antigen detection by ELISA/RDT

Rationale: According to WHO guidelines, NS1 antigen can be detected by ELISA or RDT in serum up to 9 days after symptom onset in primary infections and up to 6 days in secondary infections. It’s highly sensitive (100%) and specific (99.2%) for dengue virus detection in the acute phase.

Question 2): In secondary dengue virus infection, which of the following laboratory findings is MOST characteristic compared to primary infection?

A) Higher NS1 antigen levels

B) Rapid rise in IgG levels with reduced or absent IgM

C) Prolonged viral RNA detection

D) Higher viral load in plasma

Answer: B) Rapid rise in IgG levels with reduced or absent IgM

Rationale: In secondary infections, IgG levels rise rapidly and dominate the immune response, while IgM is reduced or absent due to the anamnestic response. NS1 antigen detection is actually reduced in secondary infections due to antigen-antibody complex formation.

Question 3): What is the preferred sample type for dengue virus laboratory testing, and what is the recommended storage temperature if testing is delayed beyond 48 hours?

A) Whole blood; 4-8°C

B) Serum; -20°C or lower

C) Plasma; room temperature

D) Capillary blood; 2-8°C

Answer: B) Serum; -20°C or lower

Rationale: Serum is the preferred sample type for dengue testing. If testing is conducted within 48 hours, samples should be refrigerated at 2-8°C. If testing is delayed, storage at -20°C or lower is recommended to preserve sample integrity.

Question 4): According to WHO guidelines, during which time period post-symptom onset is NAAT (RT-PCR) testing MOST effective for dengue virus detection?

A) 0-3 days

B) 0-7 days

C) 7-14 days

D) >14 days

Answer: B) 0-7 days

Rationale: NAAT sensitivity is highest during the acute phase (0-7 days post-symptom onset) when viral RNA levels are detectable. The sensitivity progressively declines after seven days as viral load decreases.

Question 5): A patient in the convalescent phase (>7 days post symptom onset) tests positive for IgM but negative for NS1. According to WHO diagnostic algorithm, this result indicates:

A) Confirmed dengue infection

B) Probable recent dengue infection requiring further confirmation

C) Dengue infection ruled out

D) Need for immediate NAAT testing

Answer: B) Probable recent dengue infection requiring further confirmation

Rationale: According to WHO guidelines, NS1-/IgM+ results in the convalescent phase indicate probable recent dengue infection. Further testing such as seroconversion with convalescent serum or differential diagnosis may be required for confirmation due to potential cross-reactivity with other orthoflaviviruses.